March 4, 2018

Written by Sydney Palagonia (class of 2017-2018)

This was my first Friday when observing a surgery so like normal I make my way to the conference. I see one other resident in one of the rooms, so I take a seat. 7 o’clock rolls around and it’s just me a couple other residents and Dr. Victorino. Some small talk happened till the remaining residents joined in. The conference topic was about trauma departments and how they rank compared to any other trauma departments. Highland was more in the top percent when it came down to treating theses patients that come through the emergency department. There were a few things that left highland in a grey area, meaning not in the green nor the red markers. Dr. Victorino discussed this is due to the types of tests and diagnosis that some of the residents/ doctors give the patient. These residents were taught that certain things need to be done depending on if this is happening or that’s happening. As time goes on we discover new techniques and requirements to treat patients. From this the residents/ doctors have been treating patients based on old treatments and routine tests causing highland to slip into some grey areas in treatment plans. Overall Highland Hospital is in the top percentile in the rankings of trauma departments.

I usually have stuck to operating room one and get an ortho surgery. When I went up to look at the board I decided to choose a non ortho surgery as well as a different operating room. This time I went with operating room four. The procedure was a left thyroid lobectomy. As usual I get to the room and they are putting the patient to sleep and securing him to the table. The procedure started off with a four-inch incision mid neck using a scalpel. They then proceeded using a light scalpel to open each individual layer of tissue and muscle in order to expose the thyroid. Part of the process is to detach the thyroid using a peanut forceps (which hold a small sponge at the tip), fingers, and a ligaSure jaw instrument (helps fuse vessels together).

It was a little hard to see the entire procedure since there were three residents and one attending working on a four by four area on the patients body. From what I could hear and see they had started using the peanut to go in and detach the tissues and muscle that connected the thyroid trachea. This would create extra space between the skin and thyroid. They would do little sections at a time. First using a peanut than go back over that same area using the ligasure jaw tool to fuse blood vessels so no unnecessary bleeding would occur. This process was repeated as they moved their way around the left lobe of the Thyroid. When enough of the lobe was able to come out of the initial incision, a little bit of trouble came. This is where the fingers came into use. The attending would use his finger to swipe all around the left lobe of the thyroid to feel and possibly detach what was missed in the first place. The left lobe of this man’s thyroid was roughly the size of a tennis ball which was another reason why it was a little hard to detach. They were finally able to get the thyroid lobe to protrude out of the incision. From this they were able to continue a similar process to detach the part of the thyroid attaching directly to the trachea. To do this part no peanut or fingers were used. Instead a simple action of forceps and a curved hemostat were used. The surgeon would use forceps to pick up a small section of tissue and poke the closed curved hemostat through the tissue and open them to create a hole. This would detach the tissue from the lobe of the thyroid. This was done around larger blood vessels so that way they could use the ligasure jaw to cut off the blood flow. Roughly another hour went by and they were finally able to take the left lobe of the thyroid of this patient completely.

January 2018

Written by Katherine Lam (class of 2017-2018)

I arrived a bit early in the morning, nervous and confused, trying to find to the lecture room. There was a door to which I could not badge in, but luckily one of the doctors had found me wandering around and made the correct assumption that I was apart of OREX. She badged me into the hallway and lead me to the room. I was the second to arrive, but med students and residents quickly arrived and took their seats at the table.

The case study for that day was about research regarding the “step up approach” for necrotizing pancreatitis, or pancreatitis where pancreatic tissue starts dying. They discussed why it was worth studying (because the traditional treatment for necrotizing pancreatitis had high mortality/morbidity), and how the results of the intervention. They also discussed some background of the disease: its etiology was alcohol or gallstones; the gold standard to diagnosis was FNA culture; initial orders for this diagnosis were fluids, IV, foley, and NPO; CT scans of the body showed enlarged pancreas. It was all very interesting as I had never heard of necrotizing pancreatitis.

I moved to the OR floor, again feeling a little lost. One of the residents was very nice to show me where I could find the vender card and how to use it to retrieve scrubs. I also met nurse Julie who sensed my obvious inexperience and showed me where to find the necessary gear and rooms.

The first procedure I had the chance to observe was a Port-A-Cath placement. I took my place at the side of the room, but I ended up moving to the other side as large machines for X-ray and imaging monitors were maneuvered into the room. The nurses gave me a lead vest to wear during the procedure. The patient came in, as well as anesthesiology who explained that he was giving her some medication to help her relax. She quickly fell asleep from the sedative. The nurses proceeded to tie down her body and tuck both arms into her sides to prevent falling. She was given oxygen through a mask, but ended up being intubated. An ultrasound machine was used to view the neck vessels for any signs of clots or intrusions. They read out patient info, and the procedure she was here for, and finally started the procedure at around 9:00 AM. The nurses and the surgeons were very fluid in working as a team, to my surprise. They began with a small incision in the chest area and made a “pocket” under the skin for the port. They used a long spear-like metal instrument to guide the catheter under skin and clavicle to enter the vein. X-ray imaging was used to check positioning of the catheter in the left ventricle of the heart. They used heparin to “lock” the catheter. After port placement, they closed and stitched the incision. The whole procedure took around an hour to complete. The patient was decannulated and woke up in a panic. As the anesthesiologist was trying to calm her, they moved her out of the room so they could begin cleaning.

I was again confused where I should go next, but the nurse told me I should stay for the next procedure, which was after lunch. It turns out the next procedure was an ORIF, or Open Reduction & Internal Fixation, of the left zygomatic and tooth extraction. After preparing the room, the patient was moved in and given sedative and oxygen. He was also given some nasal spray (I was not able to catch what it was or what it was for). His eyes were taped shut with a sheet of plastic dressing (tegaderm) and his face was cleansed with iodine multiple times. His mouth was stuffed with gauze and cleansed with mouthwash and toothbrush. They marked the artery at the temple and injected numbing medication. A small incision was cut at the mark while blood was suctioned away with a tube. When a large enough hole was made in the skin, they stuck a long flat tool into the hole, under what I presume to be the zygomatic bone, and pushed it outwards from the head (which is when I started cringing). Clear liquid started dribbling out of the hole and suctioned with the tube. When finished draining, they stitched the incision. They continued to the next operation to extract teeth. They injected numbing medication into the gums and started yanking out teeth. It was noted that his blood pressure was rising very quickly which is a sign of the patient being in pain. They quickly finished up and stitched the gums. The entire procedure lasted around 1.5 hours.

The last procedure I unfortunately did not get to see from the beginning. The procedure was for a diverticulitis laparoscopic sigmoidectomy.The lights were off in the room with two monitors and multiple people surrounding the patient. On the monitors I could see what appeared to be the guts (intestines and surrounding organs) of the patient. The nurse explained that the patient’s abdomen area was currently inflated with CO2, and had a couple “ports” or holes to ensure that the abdomen was “air tight”: one large “gel port” for hand access, one port for the camera, and one for the cutting(?) instruments. It was a bit hard to tell exactly what was going on on the screen, but I could see an organ getting cut/separated from another. After the procedure the nurse and surgeon had explained that the patient had diverticulitis, or inflamed small pouches, in the sigmoid of the colon, and it was stuck to the bladder where a fistula was formed so he had bits of stool and blood coming out with his urine. The procedure was to take out the sigmoid segment and attach remaining ends of the colon together with a stapling tool. After the procedure was completed, they removed the tools and stitched up the holes in the abdomen. I was able to see the sigmoid that was just removed, and the surgeon cut it open to point out the characteristic diverticula. This procedure was definitely the most interesting and educational experience for that day. I was very grateful that the doctors, nurses and staff were all very friendly and open to OREX students, and I can easily see that they encourage an environment of learning and education!

Thanks for the opportunity!

January 20, 2018

Written by Jonathan Li (class of 2017-2018)

For my third OREX day, I was able to coordinate a day in the Orthopedic Clinic with Dr. Krosin. Since I had arranged to meet Dr. Krosin at 9 AM and the one hour gap between the morning general surgery meeting and our designated meeting time was not enough to observe a full surgery, I elected to wait in the OR breakroom, reviewing some anatomy on a website a medical student had recommended to me on my last OREX day and talking to some of the doctors and nurses who trickled in and out of the room. At 9, I headed up to the 7th floor, and a nurse at the front desk kindly brought me into the clinic. Dr. Krosin was nowhere to be seen, but Dr. Vogle was in and gave me a brief introduction to the daily routine in the orthopedic clinic and the subspecialties of Highland’s orthopedic surgeons (there are few who specialized in hand surgery and a few others in trauma). Dr. Krosin appeared about half an hour later (the orthopedic surgeons had their own morning round and set of meetings), and we began seeing patients immediately.

Tuesdays are unique in that Dr. Krosin and most of the other orthopedic surgeons spend the day seeing patients in the K7 clinic rather than performing surgery in the OR. Thus, this was a valuable opportunity to see what goes on behind the scenes of an orthopedic surgery and learn about the orthopedic clinic’s services. The pace was much faster than the operating room (patient check-ups averaged roughly 10 minutes), and I did my best to keep up with each patient’s situation and background. Despite the quick pace, Dr. Krosin did a good job painting a picture of the broad categories of services provided by the orthopedic clinic. The primary services provided by the orthopedic clinic include chronic pain management, post-operative follow ups, and pre-operative evaluations.

A good fraction of patients were visiting for chronic pain that did not require operation. In general, these patients’ treatments consist of joint and/or soft tissue injections (i.e. with corticosteroids for anti-inflammatory purposes) every few months. In between patients, Dr. Krosin would comment on the cases and provide advice on entering the medical field. For example, Dr. Krosin pointed out that some of these chronic problems would be better solved with lifestyle changes. As we progressed through multiple cases with patients receiving these injections and leaving with prescriptions for pain relievers, Dr. Krosin also brought up the current opioid crisis and how opioid addictions tend to start. I wanted to press Dr. Krosin more about this issue and how it applies to Highland Hospital, but I did not get a chance to discuss it in much detail. Nonetheless, it was beneficial to begin comparing how the opioid crisis is perceived from someone outside the medical field to that of a physician directly dealing with patients in serious pain.

Another set of patients were visiting the clinic for post-operative care. One interesting case involved a patient who had developed an allergy to the material composing her knee replacement. According to Dr. Krosin, the patient’s specific allergy was quite rare, and a ‘revision’ was in order to swap out the knee replacement with one made from a different material. I found this case particularly interesting because it brought to mind our body’s response to the synthetic/foreign materials orthopedic surgeries often introduce and how faulty responses could lead to pathology. Another patient had recently undergone a dermofascioectomy for Dupuytren’s Contracture. Dupuytren’s Contracture is caused by the abnormal thickening of tissue in the hand and results in difficulty straightening affected fingers (usually the pinky finger and the ring finger), and a dermofascioectomy attempts to solve this by removing the thickened tissue and replacing it with a skin graft to help restore hand movement and finger agility. Unfortunately, the patient’s post-operative recovery was not positive, and physical therapy was prescribed to help with post-operative recovery and restoring dexterity.  (https://www.webmd.com/arthritis/ss/slideshow-treatment)

(https://www.webmd.com/arthritis/ss/slideshow-treatment)

Adjacent to the clinic is the ‘cast room’, where patients’ injuries are examined and their casts altered or replaced as necessary. Some patients in the ‘cast room’ only needed to briefly touch base on their recovery progress while others were being evaluated for surgery. On a few of the checkups in the ‘cast room’, I shadowed one of the orthopedic chief residents, and the resident was kind enough to walk me through a few X-rays he was examining to determine the patient’s recovery and/or whether surgery was necessary. After most of the patients in the ‘cast room’ were taken care of, I followed the resident to the OR, where I observed a thumb amputation to end my day.

All in all, I enjoyed my third OREX day and the valuable perspectives I gained by spending time in the Orthopedic Clinic. I am especially grateful to Dr. Krosin and the orthopedic residents for welcoming my observation and showing me another dimension of orthopedics care.

December 31, 2017

Written by Man Kim Phan (class of 2017-2018)

I got to Highland super early today and got myself situated in room 230 half an hour before the morning meeting. At about 7:10 am, residents started trickling in, but the attending was still not here. Everyone decided to wait 5 more minutes but the attending still hadn’t shown up. And so the meeting was cancelled as people dispersed to grab early breakfast. I gotta admit I was really disappointed as I was curious as to what the Wednesday’s lecture could be about. I went to the cafeteria and waited until the first surgery.

Once in the OR, as I was checking out the schedule of surgeries on the whiteboard, an intern, whose name I recalled was David Liu (?), was also there wondering which surgeries he should observe for the morning. He gave me a brief overview of each type of surgery listed on the board and gave me advice on which one I should watch. He said if I’m interested in seeing surgery, then a laparoscopic cholecystectomy would be ideal as there will be a camera; on the other hand, if I’m interested in learning about surgical procedures then any of the orthopedic surgeries would be extremely informative. He was personally interested in a case on unclogging the arteries of an elderly patient that might involve complications (I couldn’t catch the names of the procedures) but the patient wasn’t there yet. Since this is only my second surgery day and I hadn’t seen a lot of surgeries yet, I took his advice to catch the cholecystectomy.

The surgery already started when I got into the room. The circulation nurse kindly got me up to speed with what was going on. On the screen, I could see the gallbladder, a dark red mass of tissue covered with fat and layers of connective tissues, and the liver in the back. The surgeon was delicately “peeling” away the peritoneum (I think…) with heat! At the same time, I overheard them looking for the cystic duct and artery. After some time had passed, the surgeon encountered a thin pale white duct slightly inferior to the gallbladder as the gallbladder was flipped over. Upon close examination, I think they determined that it was the cystic artery, and the surgeon ligated it with a clip. Furthermore into the dissection, as more layers of tissues were peeled off, the surgeon located the cystic duct, slightly larger in diameter than the artery. The cystic duct was also ligated. Then, both ducts were cut. At this point, he finished up dissecting the gallbladder from its attachment to the liver. I think the tool he used was also heated as it left the surface of the liver with shiny, metallic-looking traces everywhere it touched. As the surgeon moved away, I started paying attention to the three port insertions on the patient’s abdomen and realized how incredible it was to be able to operate on the internal anatomical structures of the human body through only three small incisions. I witnessed the gallbladder completely detached from the liver and safely placed in a specimen bag- this process was still going on inside the abdomen. I couldn’t see how the specimen was sucked out, I assumed through one of those three “holes”. Then, I noticed the patient’s abdomen was unusually inflated and flaccid but did not give it more thought as to why. Later on, as I looked up written explanation of this procedure, I found that the surgeon must inflate the patient’s abdominal cavity with carbon dioxide after initial incisions to create easier access. This was the preparation step that I missed but I was in awe that a seemingly insignificant detail that the eye of an amateur, aka me, did not catch does matter in the course of the surgery. Everything all made more sense to me.

As the first surgery was over, the nurse recommended me to watch some orthopedic surgeries so I went to OR 1 where Dr. Liu was. Before entering the room, I made a quick observation of what everyone was wearing from outside the room and noticed the CT machine. I went to grab a lead vest and was told that the purple vests are the lighter ones (“small” people take note!).

This time, an Open Reduction and Internal Fixation of Distal Femur (ORIF) was in progress. This room had a completely different atmosphere than the room I was in earlier- more vibrant and almost hectic as surgeons shouted out instructions and, every now and then, words of motivation. And unlike in the previous surgery, the surgeons and med students were all operating with large tools such as long needle-looking nails, screw, metal graft, etc. I could see quite an amount of blood on the patient’s lower leg which got onto the CT machine and all over the floor. At the moment, a surgeon was pulling from the patients’ leg as others adjusting the positions of the nails and metal plate. I could see the CT scans taken at every step although I could not tell at all what the changes in positions of the bones or the instruments were. I could, however, make out the fractures around the medial epicondyle of the femur. I couldn’t tell what was going on during most of the procedure but some quick Google searches helped me understand the overall steps involved in an ORIF. Basically, this procedure is used to treat bone fractures. The broken pieces will be aligned and secured with screws, metal plates, wires, or pins. The surgeons were incredibly meticulous, making sure every pieces of metal was in the exact position. Countless CT scans were taken until the surgeons were satisfied with their work. This process took about four hours. Toward the final stretch, the patient started regaining some sensation so the nurse and Dr. Liu gave the patient some injections through the IV. I actually did not realize the patient was awake until half-way through the procedure. The patient was only given local anesthesia. The nurse and Dr. Liu continued comforting and checking in with the patient over the blue shield. I could not imagine what the patient must have felt throughout the surgery but I’m glad the staffs were really supportive and professional. Someone shouted out, “Final stretch,” as the head surgeon secured the last walkers (like some sort of screw that secures the metal plate in a position laterally along the femur). Other surgeons quickly sewed up the patient’s skin and cleaned up the blood. The surgery was being wrapped up as the head surgeon asked the CT tech to take a couple final shots of the femur where the metal plates were. At that point, the room was getting rather crowded as the staffs were working on transitioning to the next surgery so I just excused myself and headed out. There weren’t any more surgeries besides a couple of cataract removals so I decided to call it off, amused and inspired by what I have observed and learned today.

November 30, 2017

Written by Tashma Greene (class of 2017-2018)

When waking up on the morning of my first day, I was beyond excited. The first mental note I made after silencing my 6:00 am alarm was “Tashma, please make sure to eat breakfast and stand up straight all day long”. I was able to get down at least two blueberry waffles, hit a shower and ultimately hit the door. I arrived at the hospital promptly around 6:50am and shot to the OA-2 Wing alert and ready to rule the day. Once I entered the very first door to the OA-2 Wing to congregate with the residents for lecture, I was left to find an empty hallway with several doors closed but one. I was greeted by a nice woman named Emily. After viewing the sudden estranged look of defeat and confusion on my face, she immediately said “It must be your first day of the OREX Program. Follow me!” My power was then rejuvenated inside of me and I was once again ready to win the day. After making small talk with Emily during the walk over to the meeting room, which my badge didn’t work for, I was in a room surrounded by residents and other medical professionals. I was amazed.

The 7:00 am lecture was ready to start and the topic of the day was “blind breast cancer”. I felt ecstatic to know that I was somewhat aware of the modern medical practices involving breast cancer, few statistics and also had been trained on how to perform a self-breast examination. I thought to myself, “Yes! I can be apart of the conversation!” The lecturer opened the floor to the many sleepy but focused residents. The lecturer began the conversation around presenting cases to the students to get their current evaluation of how to access a patient. The first case presented was shaped around a 27 year old woman who complained of a lump in her breast and has had repetitive visits to her daughter out of sense of concern. Simone, one of the residents that was extremely nice to me throughout the day if I might add, mentioned the following step by step by following the “triple test” evaluation: physical examination, patient preference of care and biopsy. The residents focused on the requirement of characterizing risk, population risk versus high level risk to support the step by step process. The second case presented focused on a 59 year old woman who complained of the same issues presented in the first case; however, the residents and lecturer agreed that women over the age of 40 are more likely to be susceptible to breast cancer and should receive annual mammogram examinations. I became aware of new terminology to characterize breast cancer screening processes such as benign, LCIS, DCIS and the classifications of Birad testing from levels 0-5. I learned from this lecture the importance of taking notes and observing the conversation to be afforded learning of the topic.

After the lecture, I became aware that the lovely Emily who escorted me to the morning lecture is actually an attending at Highland Hospital who is known as Dr. Meraflor. Dr. Meraflor escorted me to retrieve my scrubs for the morning and suggested that I attend the rectal surgery in OR 4. Dr. Meraflor was performing a surgery on a 52 year old male patient who had been diagnosed with HIV and without treatment he’d received 2 months prior would have been positively tested of AIDS. The rectal surgery was being performed with the objective of ceasing stool drainage from a lesion that had developed adjacent to his inner right buttock. The patient was also in need of his 5 month follow up examination, which also influenced him to come in aside from his developing legion. Dr. Meraflor with the assistance of resident Dr. Cohan used a probe to locate the bypass of bile secretion through the patient’s anal sphincter to the infected lesion. Once finding the connection between the anal sphincter and the lesion, they weaved through a specialized rubber band to protrude directly through the lesion. This rubber band was inserted into the lesion to support the drainage of the lesion to avoid it developing into an abscess and further complications due to his compromised immune system. During closing, both Dr. Meraflor and Dr. Cohan decided that after securing the rubber band connection to cut the excess exterior tissue to support the cleanliness of the area. After the closing and dictation of the surgery, I was able to ask Dr. Meraflor was how would the recovery treatment plan be for the patient post surgery. She informed me that the patient would endure quite a bit of pain and would have to adjust his life around his new appendage to his anal sphincter. She also proposed that this patient would have a follow up visit within the next few weeks.

The second surgery of the day was a umbilical hernia operation conducted by Dr. Bullard and resident Dr. Cohan on a 54 year old male patient. The doctors proceeded with making small incision at the umbilical area of the patient’s abdomen mainly through fascia. The left side of the incision possessed the exposed hernia, which left both doctors to question the precision of the previous surgery. It was then brought to my attention that the patient had undergone surgery for a hernia within the past year. Therefore, this surgery was considered a hernia repair by the surgeon. Dr. Bullard expressed that if the patient was to endure another hernia, the next option would be to amputate the entire left side of the infected area due to the lack of precision of the initial surgery. During the grafting process, Dr. Bullard instructed the circulatory technician to obtain a hernia patch. A hernia patch is a self expanding bioresorbable coated permanent mesh patch. At closing and dictation, Dr. Cohan was able to explain to me that the patient would not be able to execute any heavy lifting due to the healing process of the mesh patch ranging between 3-4 weeks. This surgery was a less invasive procedure, which left me with more questions after closing. Dr. Cohan then explained to me the different hernias that patients could experience ranging from inguinal, incisional, umbilical, hiatal and femoral hernias.

The third and final surgery that I was able to attend during my first shift was a laparoscopic right hemicolectomy surgery. The operation was being was conducted on the right colon of a 52 year old female who suffered from colon cancer. The difference between this surgery and the first two I observed was not only the differentials of the case but also the method that this surgery was conducted. The surgery was conducted via microscopy equipment which is known to be less invasive, produce faster recovery time and allow the patient to feel less pain post-surgery. Dr. Meraflor conducted this surgery with the assistance of Dr. Swanson and Dr. Goloroski in OR 4. The objective of this surgery was to remove the right colon that had been previously tattooed by the GI Department as a potential mass tumor. During the surgery, Dr. Meraflor mentioned important hints to the residents during the procedure such as preserving the mesentery tissue and to keep the colon from infarcting. The residents proceeded to remove the right colon via grafting and made it to the final step prior to extraction of the right colon, which was to create a bypass for the existing colon. Dr. Swanson proceeded carefully to chaft two holes into the left colon to later staple them together and utilize silk thread to solidify the new passageway for the colon. To remove the right colon Dr. Swanson made a small incision towards the lower abdomen of the patient and removed the right colon. When removing the specimen, Dr. Swanson identified a portion of the small intestine, cecum and appendix that were removed from the patient. The specimen appeared to have a soft texture and was removed with adipose tissue surrounding the exterior of the organ. The specimen would later have its lymph nodes and if the results test positive for cancer the patient will have to begin chemotherapy sessions again to prevent the spread of cancer.

November 11, 2017

Written by Krishan Banwait (class of 2017-2018)

First, I would like to thank Lucy and the amazing OR staff for the opportunity to observe surgeries and learn about how the OR functions. I learned a lot and I am eager to return for future surgery observations. I observed two surgeries, the first involved the insertion of a screw into an elbow joint, and the second involved the removal of a gallbladder.

In the first surgery I entered at around 11:15am for the start of the surgery and watched as a team (two nurses, a nurse anesthetist, an anesthesiologist, and an orthopedic surgeon attempted to calm an 89-year-old man. The man spoke Mandarin and had dementia. One of the nurses attempted to translate what the team members wanted to communicate to the patient since she was the only Mandarin-speaker in the room. The patient was very uncomfortable and due to his weak heart he had an ongoing myocardial infarction (blocked blood flow to the heart). The team decided not to intubate the patient, since this would increase his chances of death. Instead they sedated him and covered him with the blue sheets (which indicate sterile areas) and then created a hole for his right arm to go through the sheet so they could operate on it. In addition, they had already inserted a urine catheter (to gather his urine and avoid him accidentally emptying his bladder) before I entered the operating room.

The patient’s right elbow was badly cut and skin was torn off the back of his right hand. The surgeon at first considered doing a skin graft by taking skin from his left calf, but decided it was not necessary and could create a higher risk of complications. Thus, the surgeon did two things: 1) physically pick out any debris in the back of the hand and in the elbow area and 2) inserted a screw in the elbow since the bone had been damaged.

After painstakingly removing every small fragment that could be found the surgeon drilled a thin hole in the patient’s right elbow into the humerus bone and then inserted a single 7 mm screw. The surgeon used a thin drill bit and tools that a carpenter would use. After he finished inserting the screw, the doctor took an x-ray to test that the screw was in the proper place and the humerus was not damaged. Next, the surgeon sutured up the elbow with three long pieces of thin wire and used water to wet plaster wrap and create a cast. The reason for using plaster was because the cast would adhere to the sutures better than alternative materials. The plaster cast was meant to be temporary, thus fiberglass was not a good material to use. After finishing the cast, the doctor wrapped an ACE bandage around it.

The anesthesiologist and nurse anesthetist laced a central line (or central venous catheter) into the patient’s neck vein. They had me read out to the nurse anesthetist when the computer monitor’s readings dropped below 300 mL/minute, since her view of the monitor was blocked while she helped the anesthesiologist place the central line. A reading below 300mL/minute indicated catheter dysfunction. After placing the central line, a nurse noticed the patient had dentures and his lower ones were coming loose. Thus, the nurse pulled the lower ones out and put them in a container.

I joined the nurses and nurse anesthetist when they walked the patient over to the ICU. I watched for about 10 minutes just outside the room as a group of doctors and nurses from the ICU rushed into the room to learn about the patient, monitor his vitals, and decide what to do next. They also decided they would remove his upper dentures, which were firmly stuck in his mouth.

One good piece of advice- you will find the booties and hair covering in boxes in front of the administrative office on the right after you enter the first double doors into the operating room area (just past the OR board, which lists the surgeries and is located on the left of the hallway right after passing the first double doors). In the men’s locker room (and likely the women’s too) you can put all your items in your backpack and leave it on chairs in the locker room (other backpacks were there) since the lockers may all be full and locked. Plus, you can hang up a jacket, if you bring one, on the hooks besides the locker. Do not forget to grab your jacket before you leave, like I did. My jacket was still hanging on the hook when I returned two days later, (so you should be fine if you accidentally leave something in the locker room for a couple days).

In addition, do not forget to grab a face mask (you can use the pink-colored/clear droplet masks that are also stocked in the SDU and Med-Surg departments). They are located just outside the operating rooms, at the sink attached to the main hallway, (before you turn right in the hallway to go towards OR #1 and #2). These droplet masks will provide a clear plastic visor that protects your eyes, and are recommended although most of the staff will likely wear the yellow-colored masks that only cover the mouth area. If any x-rays are taken, remember to grab some lead-containing vests that have Velcro straps and wrap around your chest. They are necessary to limit the effects of radiation. (They are more bulky and heavy duty compared to the typical vests you wear in a dentist’s office when you get your teeth x-rayed and can be found outside OR #2 in the hallway. Do not grab one that has a doctor’s name printed on it).

The second surgery involved the removal of a gallbladder. I walked into the operation in OR #2 in the middle of the operation. It was a laparoscopic surgery and involved three small holes made in the patient, two holes were for tools and the last hole was for a small camera that snaked in on a thin, long wire. One of the two tools inserted had a clip on the end that held a piece of tissue away from the gallbladder so the camera had a clear vision of sight and the gallbladder could easily be accessed by the second tool. The second tool was a hook (a bent tool that had nearly a right angle) that was used to pull at loose tissue of the gallbladder and it also created a heated spark that would burn tissue and create a small stream of smoke. The hook tool was used to pick apart at damaged gallbladder tissue with the aim to create several holes in the gallbladder to help slowly break down the organ and create easy removal.

The surgical team inserted metal clips that held sections of the gallbladder together. There was a damaged thin line on the gallbladder that resembled bacon. The line was brown/white and looked dried/crusty. The team was working to separate the gallbladder from the liver to aid in removing of the gallbladder without damaging the liver. It was interesting to see the different organs and the similar reddish/orange color that each of them had. I watched the surgery for about one hour and did not get to see it finish, but I was very intrigued by the meticulous, slow process that involved using small tools to slowly snip away at the relatively large organ. It was also interesting since there were two monitors showing the same camera image and a few residents that were discussing the steps of the surgery with the attending and the chief resident.

November 21, 2017

Written by Tanya Joseph (class of 2017-2018)

I was standing in the lonely hallway on OA-2 at 6:30 am unable to decide which door to badge in when I bumped into Dr. Victorino. I kindly introduced myself, and he directed me to the glassed door in front of the department of surgery. My badge did not work there, so I went to OA-3 and had enough time for a coffee at the vending machine in OA-3 to kick-start my day. I came back down to OA-2 and an internal medicine physician saw me stand confused and unable to badge in, and she was so kind to let me into the Resident City with her badge. While making myself slowly familiar with the resident faces, I realized they were all very alert and attentive for an early morning class. The vibe was a very enthusiastic one, and it was more like a case discussion rather than a class. Slowly the room was full with 13-14 people inside sitting around the conference table, including medical students and attending, Dr. Victorino. I was amazed how friendly he was to the team of residents and students. The flow of topics from him totally convinced me that he was a very experienced surgeon. I became more eager of the topics that he came up with.

The class began with discussion of a case that came in the Emergency department the previous night. A middle-aged man was brought in with loss of consciousness, and fixed pupils after a head injury. His distal pulses were feeble and he was intubated because of signs of aspiration. His chest X ray showed an abnormality in right upper lung lobe. The questions followed after one of the resident presented this case. Dr. Victorino made sure that he asked each and every resident a question regarding the case. The first question was, “What do you think the problem was, what are the differential diagnoses, what will you do next- EKG, Blood labs?’’ All the residents were prompt with their answers regarding the pathology, diagnosis and treatment. They discussed how this could be from a previous medical condition and not purely a result of the traumatic event. From their discussion, I figured that it is good to have a perspective opinion from an internal medicine physician in such cases. They discussed what the ER team did, in order to resuscitate the patient and then went on to start discussing about the treatment for hyperkalemia since the patient’s potassium levels were very high (7 mEq/liter). Hyperkalemia occurs when serum potassium levels are more than 5- 7 mEq/Liter and it could precipitate cardiac arrhythmias. If serum potassium levels are high, your aim is to stabilize the heart, treat with insulin to drive the potassium back into the cells, kayexalate, calcium gluconate, and ringer lactate. Normal saline should be avoided because of risk of metabolic acidosis.

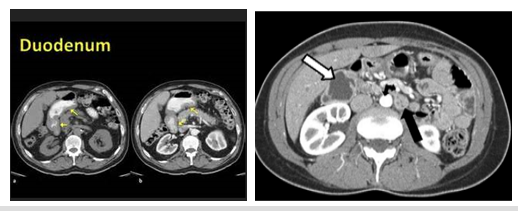

They later went on to discuss another case of an 82 year old lady with duodenal rupture that caused the contrast agent (gastrograffin) to leak. She was previously brought into the ER for bilious vomiting and constipation for 4-5 days. She had a previous history of stroke according to her daughter. The surgeons were concerned about mesenteric ischemia (lack of blood supply to the intestines making the perforation difficult to heal) due to past history of stroke and her age. She was scheduled yesterday for an exploratory laparotomy and repair of the duodenal perforation. They would repair it with the patient’s omentum. They discussed briefly the CT scan of her abdomen. The first picture is of the CT abdomen showing duodenum.

I tried to find a picture similar to the contrast leak that was shown in class in picture 2.

I hardly got any time to talk to a resident as everyone dispersed immediately after the class, and I walked to the OR. I had read Lucy’s recap of orientation many times and this helped me get to exactly where the vendor card was. There was no one at the station, so one of nurses (Mark) helped me get the card and he understood that it was my first day. He walked me out to the changing room and showed me exactly how I could get my scrubs and gave me instructions about the hair cover cap. The red line to the OR can be crossed only if your head is covered and you have a mask on. I also covered my shoes with the shoe cover.

Later I found myself staring at the board to decide which surgery to go and observe. I wanted to tail Dr. Victorino and I stepped into OR # 3 for Right heart catheter implant. I stepped into the room and introduced myself to the nurse (Monica) and I wrote my name on the board. She was so sweet that she personally took me out to get the X-ray shield and said to have it on all the time that I was there. There were totally 6 of us in that room and Dr. Victor said, “Whoever is in OR 3 should stick to OR 3.” All the time I was very careful not to touch the sterile blue area. The X ray tech asked me to get a thyroid protection shield but they were all in use, so he was very kind enough that he offered me his shield. The surgery was performed by a resident under the guidance of Dr. Victorino. The atmosphere in the OR was calm and everything went smooth. The procedure was short and finished sooner than I thought.

Overall, my day was very good and I was happy that I learned a lot. Later I stepped out and thanked Dr. Victorino and he mentioned that we are welcome to attend lectures on Wednesday mornings in the Old Building. They teach different topics on Wednesdays. I did not come across Nurse Julie the whole time, so I think she must be off for the Holidays. Everyone whom I came across was very helpful and kind. The only times I fumbled were to get hold of the Vendor card and I did not know where to put away my used scrubs, so I placed them in the blue cover in the changing room that I assume is for used scrubs.

November 19, 2017

Written by Jonathon Taylor (class of 2017-2018)

“Cause it’s a bittersweet symphony this life.

Trying to make ends meet, trying to find some money then you die.”

-The Verve

Among the many things I learned during my first OREX day is that Dr. Ito, the urologist performing the cytoreductive radical nephrectomy, has excellent taste in pop music. Nary a repeated tune as his phone played the likes of Beyonce, the Verve, and Prince. Several hours into the process, and despite my best attempts at professionally representing both the Highland Volunteer program, and OREX, I admit that I quietly sang along to Raspberry Beret while standing on a step stool to get a better view into the dissection as Dr. Ito and Dr. Yamaguchi worked to remove the football-sized kidney from their patient.

I arrived at the O.R. after Grand Rounds in time to watch as the patient, a man in his mid 40s, was being prepared for surgery. I stood at the back of the room, facing the foot of the bed and observed as William, an OR tech, carefully set out the sterile tools. I took notice of a corrections officer in the back corner, and then turned my attention to the center of the room, where the patient sat on the edge of the bed, fully tattooed, back exposed, in preparation for an epidural. A CRNA named Rebecca was seated in front of him, quietly and very gently guiding him through the severe pain he appeared to be in while holding both of his hands in what struck me as an extremely empathetic gesture. A CRNA resident was administering an epidural using a glass syringe[1], but this man’s pain was profound, he could barely bend forward enough to expose the spaces in his vertebra. His right kidney was all tumor, compressing his spine, making every movement a painful chore.

The atmosphere of the room was sensitive and respectful of the patient throughout the procedure, but shifted into an animated, positive and professional tone once the patient was under anesthesia. Wendy, the circulating nurse, generously provided me with a running commentary during the preparation and initial dissection. Before the first cut, there was a palpable pause in the action, Wendy explained that this is the timeout period, part of “Universal Protocol”[2] designed to help avoid wrong-patient and wrong-site surgery. Also, she said, it allows time for the alcohol used to prepare the incision site time to dry, otherwise the electrocauter[3] used to cut through tissue might light the patient on fire…

With the assistance of resident Sidney Le, a bilateral subcostal incision was made through the epidermis as part of the anterior transperitoneal approach to renal tumor excision. After cutting through the dermis, adipose tissue, muscle and finally the peritoneal lining, the surgeons were able to see the kidney. William explained that The Verve were sued by the Rolling Stones for the melody of “Bitter Sweet Symphony”; Mick Jagger and Keith Richards now share a songwriting credit for that catchy tune.

A large ring, to which various soft tissue retractors were attached, was placed above the patient’s abdomen to keep the cavity open. My rudimentary understanding of the excision is that the renal artery and vein, which run medially to the kidney were clamped, as well as the ureter which runs medially and distally. The surgeons used color-coded bands to identify the anatomy to be cut. At some point each surgeon took a turn reaching around the posterior side of the kidney to help free it for the final part of the removal. Meanwhile a discussion ensued about the state of Mariah Carey’s voice, apparently her technique has had a detrimental effect on her singing voice in the opinion of some.

Doctors Yamaguchi and Ito explained that the massive posterior tumor had already metastasized. Current theory posits that removing the kidney allows the immune system to concentrate on the metastasis. Perhaps more importantly in this case, the surgery provides symptom reduction which will hopefully allow this man to live in less pain for the statistical one to two years he has left to live. The Spanish word ‘profudo’ entered my mind as I first peered into the dissection – the term is used to describe both the physical depth of an opening and also the effect that something has on the soul. This was the first surgery I’ve ever witnessed and it was the first time that I’ve simultaneously felt enthusiasm, fascination, and ultimately sorrow. I do not know what this man did, nor do I know if he will spend the rest of his life incarcerated. What I know is what I observed, that every person in that room did all they could to provide another human being with some level of comfort and relief, and treated him with dignity and compassion.

Terms Learned

- Cytoreductive surgery: surgical procedure used to remove tumors. Cyto (greek) = cell

- Nephrectomy: kidney removal. Nephr (greek) = The kidney, -ectomy (greek) = cut out

References