Author Archives: Lucy Ogbu-Nwobodo

July 28, 2017

Written by Olincia White (class of 2016-2017)

My July OREX day was most exciting. I realized that it is not solely about which surgeries you observe but also greatly about who you meet and the opportunities that arise. On July 28th I arrived to Highland and decided to observe a surgery with Dr. Richard S. Godfrey. Having had observed him once before I jumped at the opportunity to join him again. We made brief conversation after board rounds and he welcomed me into the OR. The surgery was for a young woman who had a mass in her left breast. The mass was small and was assumed to be benign based on the size, the even edges, and the lack of pain associated with it. Most cancerous masses will have a jagged edge, be asymmetrical and cause pain and discoloration. This was a mass about the size of a peanut M&M. It wasn’t too big but it was hard and worrisome. The surgery was being performed by a new resident who was getting his first chance at excising a mass at Highland. He was being supervised by Dr. Godfrey and one of his senior residents, Dr. Simone Caccano. Dr. Godfrey assured Simone that she had done the surgery enough times to teach the new resident so she did. Every time Simone asked the new resident if he had done something or used a certain instrument before, he replied “not at this hospital” he was very quiet and I wondered if he was nervous but why wouldn’t he be? Surgery is a very intimidating process. One thing I’ve learned is that no matter how smart you are you must humble yourself for surgery. The new resident was Dr. Kevin Machino and as the surgery unfolded Simone did more and more as he sort of stood back and observed. It takes some time to get used to using the trochanters and tools in a manner that’s pleasing to the seasoned residents and doctors. Before long, the mass was out and the patient was being stitched up. During the surgery Dr. Godfrey came over to talk with me. We discussed my interests in surgery and medicine and he shared with me some very amazing and life changing news! To my surprise, Dr. Godfrey is the author of a book, “African Queen, Tales of Motherhood and Wild Bees”, a story of the Obama family, three dynamic Kenyan women, and their impact on an evolving culture. The book discusses how societies handle the challenges of resources, population and climate changes.

In addition to the book Dr. Godfrey is the creator of a free clinic for women and children in Kenya! He gave me his card which has the title of the book, and gave me information on how I can volunteer… in Kenya! The clinic is the Matibabu Foundation hospital and there is an organization here in the bay area that I can volunteer with if I am interested in going to Kenya myself. We discussed plane tickets and the process involved. How exciting is that?!! This encounter truly made my day and opened my mind up to a whole new slew of possibilities. In the near future I hope to contact the organization and volunteer. It has always been my dream to help women and children, especially those who are less fortunate or living in an underserved community. Who knows maybe one day I’ll go to Africa and give back. If I do it will be thanks to the OREX program! Thanks for reading!

August 7, 2017

Written by Courtney Pasco (class of 2016-2017)

I want to preface my summary with a quick warning: one of the procedures I saw and have described in my summary below was a D&E after a 22-week fetal demise. I know that can be a sensitive topic and skipping those paragraphs or this summary entirely is definitely an option.

The morning meeting focused on why giving blood volume can be an appropriate treatment for many different conditions. Dr. Harken walked us through the natural homeostatic response to a drop in blood volume: renin in the kidney acts as an enzyme to convert angiotensinogen from the liver to Angiotensin 1. Angiotensin 1 is converted to Angiotensin 2 in the lungs and Angiotensin 2 stimulates vasoconstriction, ADH production in the pituitary, and aldosterone production in the adrenals. ADH increases the water retained in blood, increases the feeling of thirst in the hypothalamus and aldosterone increases the amount of sodium retained in blood–all of which function to increase blood volume. The discussion went far beyond this one pathway, but I wanted to at least include this in my summary because I think it is so cool how many different (not traditionally cardiovascular) areas of your body are involved in maintaining blood volume.

The first procedure I saw was a Dilation and Evacuation after a 22-week fetal demise performed on a 30-year-old woman. The attending, Dr. Amy Kane, began by removing the gauze and grouped tampon-like packing from the patient’s vagina. Aaron, the medical student assisting her, was standing by with the ultrasound machine so Dr. Kane could have a view of what she was doing. Before placing the speculum and grasping the cervix with Allens, she mentioned that the patient was already 2cm dilated and the demise occurred almost 3 weeks prior. Next, she injected vasopressin to stem uterine artery blood loss. Then she began the suction and a huge amount of blood and tissue came pouring out. Some of the tissue was suctioned out, and other pieces were pulled out. At one point she stopped and noted that the grayish fluid leaking out was brain matter. After she was satisfied that the fetal remnants, placenta, and cord had been removed, she began scraping the walls of the uterus with a curette to remove the lining. The entire procedure took maybe 15 minutes in total.

I’m not sure how much is appropriate to share in these summaries, but I feel I should say that I wholeheartedly believe in a woman’s right to choose. This D&E was not an abortion, but I wanted to share what I felt when I was watching it with the understanding that my emotions do not come from a place of judgement. I recognize that this is a sensitive issue and I would feel a little strange only writing a clinical description of what I observed and not acknowledging that procedures like this can carry a lot of weight and emotion. With that said, I felt a lot of different things during those 15 minutes–sadness for the woman on the table, anxiety and shock at what seems like a violent, undignified end to a little life, awe at the tiny, perfect human arms and legs that were still intact (albeit strewn amongst other unidentifiable pieces of tissue) after the procedure, and finally gratitude that attendings like Dr. Kane exist and are able to give women the care they need–whether they miscarry, have an abortion, or carry the pregnancy to full term.

The next procedure I saw was a bilateral ovarian cystectomy, partly done with a laparotomy and partly done laparoscopically. The attending, Dr. Lerner, made a 2-3in incision at the bikini line and immediately located one ovary with a cyst about the size of a baseball on it. He made a small cut and inserted suction to drain the fluid. Then he cut away the cyst from the rest of the ovary and Fallopian tube. Then, using the laparoscope, they explored further up her abdomen and located the other ovary and cyst and moved it back down toward the bikini line incision. This one was totally insane. It was like the size of a volleyball and when he made the incision and inserted suction, the fluid gushed past the suction and sprayed all over the floor like a geyser. My notes literally just say, ‘Okay that was AWESOME.’ Finally, the last procedure I saw was a laparoscopic hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, which may be my new favorite word. Basically, the patient’s uterus, ovaries, and fallopian tubes were removed. This surgery just consisted of cutting around the cervix and pulling out the attached uterus, tubes, and ovaries through the vagina. However it took a couple of hours, mostly because the attending had to suture laparoscopically which took an incredible amount of dexterity and patience.

July 14, 2017

Written by Bianca Salaverry (class of 2016-2017)

My July OREX day was the most eventful one I’ve had so far. After an interesting morning lecture given by (I think) the chief ortho resident, I got to observe four surgeries.

Surgery 1: This was an irrigation and debridement (I & D) for an infection from a previous surgery. It was a fairly fast procedure, lasting only about an hour and a half. The patient came in because he had undergone surgery on his ankle not long ago and the main incision was infected. The surgeons reopened a two-inch portion of the old incision and basically just flushed it with a ton of saline. The new incision wasn’t very deep, but the doctors did make a small cut into the fascia to make sure there wasn’t any pus, which would’ve indicated a more serious infection. Luckily they didn’t find anything, and the surgery went off exactly as planned.

Surgery 2: This was one of those surgeries where I had to look up some names/acronyms in order to figure out exactly what was going on. I’m always excited by those cases because it means something new I’ve never seen before. The board called it a “Cystoscopy TURBT, and possible biliary ureteral stent placement.” A cystoscopy just refers to the insertion of a camera and light up through the urethra and into the bladder. TURBT stands for transurethral resection of a bladder tumor.

I had a great time observing this surgery because the attending performed the entire thing on her own with no residents around, so she was happy to answer my questions and talked me through a lot of the procedure. The patient came in because he had seen blood in his urine. Imaging showed that he had several large, likely cancerous tumors in his bladder. A major complicating factor here was that the man was morbidly obese. I’ve seen patients this large in the ED, but never in the OR, and once the patient was under, it became very difficult to adjust his position, which ended up being problematic. Even the initial step of inserting the camera into the urethra wasn’t working because the weight of his stomach was compressing his bladder and preventing the camera from entering and moving around easily. They called in a transport team and tried several techniques to adjust the patient. First they moved his whole body down towards the surgeon, which allowed her to insert the camera. She was still having trouble moving the probe around in his bladder though, so then they tried stretching tape from the underside of his belly up towards his shoulders to hoist it up and away from the bladder. All the adjustments added a lot of time to the procedure, which the surgeon wasn’t too happy about.

Once she had access, the doctor started to point out some of the anatomy to me. The normal bladder mucosa was smooth and pink with small blood vessels. In contrast, the tumors were clear/white and had tiny nodules with little pink dots in the center. The shape was similar to the papillary carcinomas shown here and the picture below is pretty close to what the tumors actually looked like on the camera, though in my case, the bright red vessels were absent.

and the picture below is pretty close to what the tumors actually looked like on the camera, though in my case, the bright red vessels were absent.

In order to remove each tumor, the doctor used a tool to scrape and cut them off the walls of the bladder and break them into smaller pieces. The tool also had suction attached to remove the pieces once they were small enough. In theory, this was supposed to be a fairly simple surgery, but because of the man’s size, it was hard to maneuver the tools in his bladder, and the doctor kept having to pull everything out of the urethra, so what should have taken only a couple of hours stretched on much longer. I didn’t stay until the end because the doctor kept urging me every half hour to go find something more interesting to observe.

Surgery 3: This procedure wasn’t the most eventful, but the injury was probably the strangest one I’ve seen in my whole time at Highland. The ortho surgeons had operated on this patient for a tib/fib fracture a while before (I’m not sure exactly how long, maybe a few weeks?). His wound was totally closed and the man had two ring shaped external fixators placed, one just below his knee and the other closer to his ankle. Apparently the fracture was so bad that the surgeons had to remove an entire segment of his tibia roughly four inches long. I didn’t get a chance to ask too many questions during this surgery, so I still don’t totally understand why the bone fragment was removed, but the aim of this follow-up procedure was to make some adjustments to the external fixator in order to take some strain off of the skin around the injury. I asked Dr. Krosin what the end goal was for the patient and he said that at that point, they were just doing everything they could to prevent having to amputate the man’s leg below the knee.

Surgery 4: My last case of the day was very sad. Everyone in the room was familiar with the circumstances, and some people seemed pretty upset about it. The patient was a young guy who had gotten into a car accident while intoxicated. His son unfortunately died in the accident and the man himself was in the ICU for a while afterwards and didn’t even know his son had died until several days later. He was also severely injured. He had broken both legs in multiple places and had undergone several surgeries already to repair a broken tibia and hip on his right side. This surgery was an open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) for a femur fracture. I’ve seen several ORIFs during my OREX shifts, and the most remarkable thing about this one is that there were a lot of little pieces of bone that had to be fixated, so the surgeon had to very carefully position each tiny fragment and put the end of the bone back together with the smallest K-wires they had.

There were some tough things to see during my July OREX shift, but days like this one do a lot to remind me how important it is to have compassion for patients in difficult situations, and to remain objective and give everyone the best care possible regardless of the circumstances around their medical issues.

May 31, 2017

Written by Terry McGovern (class of 2016-2017)

I hate running late and this morning I was. After concluding my last ICU preceptorship shift the night before, I had a hard time getting out of the house early enough. Compounded by especially poor parking near Highland, I was late.

Got to the rounding room 10 minutes past 7. Snuck in the side door, and sat away from the table full of residents, and was surprised to see Dr. Harken was not there. Dr. Palmer was doing a review of carcinoid syndrome. Gastric carcinoids, duodenal endocrine tumors, mid gut tumors, and the treatment of such diseases.

Oral boards are coming up soon and I imagine the senior residents are in full preparation mode.

Iheaded over to OR and looked at the board.It seems that Wednesdays are a day for oral surgery/ oral maxillofacial. Since I hadn’t seen any of those (and a couple of more interesting surgeries were postponed ) I headed to OR 4 to observe. I heard some OR joking about the fact that Oral/maxillary never use all their allotted surgery time.

First patient was a 20 yr. old male who had some severe dental issues. Impacted wisdom teeth being the least of it. The surgery was a Bilateral mandibular maxillary incisional biopsy of multiple maxillary and mandibular OKC’s

“An odontogenic keratocyst (OKC) (also referred to occasionally as keratocystic odontogenic tumor, KCOT)[1] is a rare and benign but locally aggressive developmental cyst. It most often affects the posterior mandible. It most commonly presents in the third decade of life.[2]”

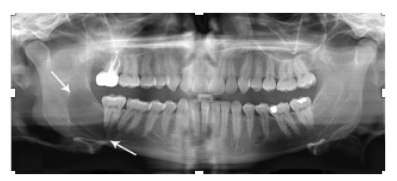

According to Wikipedia “In 2017, the new WHO classification of Head and Neck pathology re-classified OKC back into the cystic category. It is no longer considered a neoplasm as the evidence supporting that hypothesis (e.g. clonality) is considered insufficient. However, this is an area of hot debate within the head and neck pathology community, and some pathologists still regard OKC as a neoplasm despite the re-classification.” This is a typical view at what it looks like in an x-ray.

Attending was Dr. Limchayseng, aka “Dr. Louie”. When I introduced myself and told him about OREX, he humorously said “Fine with me, I don’t own the place”.

Senior residents doing the surgery were Austin Eckard DMD and Sonia Bennett DDS, and Bruce Sterling, DDS who was doing the Anesthesiology under the supervision of the amazing Dr. Jain (SP?) with the ever welcoming Glenda RN and Chelsea OR Tech.

They started at 8:50am. It wasn’t the greatest surgery to watch as you can’t see much in a patients mouth unless you are the surgeon. But it was a fascinating surgery to watch and to be able to look at the posted x-rays and imagery. I had never heard of this before so I wasn’t surprised when I found out this is a rather rare condition. Looking at the X-ray/imagery I wondered how painful this condition was pre-surgery for this young man.

Here is an image from the internet that is somewhat akin to what the patient presented with though our patient had lateralized teeth in the front in contrast to this one.

They removed a total of 6 teeth and a lot of keratinized tissue, which was sent to pathology. As I understand it, keratinized tissue displaces normal bone tissue.

Dr. Louie said that this patient definitely had a “syndrome”, which I assumed meant this was a genetic disease that was rather rare to see. One quote from Dr. Louie after noticing some less than perfect suturing, “Mediocrity is not acceptable”.

We finished up at 11:50am. A break was in order.

Since I was on their schedule, and the residents had a second surgery scheduled, I decided to watch their next oral/mandibular surgery instead of jumping into another surgery already in progress.

The 2nd surgery was a fractured mandibular repair of an ICU patient who had been hit while riding his bike. He had a closed head injury and was intubated, and due to the type of surgery they had to intubate him thru his nose for the surgery. There was some concern that due to the patient’s closed head wound/trauma that they would want to do this surgery as quickly as possible to avoid any complications or Inter-cranial pressure increase.

Attending was Dr. V. Farhood, who was a very welcoming and lighthearted surgeon, who was also supervising a surgery in another OR simultaneously’ .

Officially called an ORIF of Mandible Fracture post car accident, and start time was around 12:30pm.

The most interesting part of this surgery was that the surgeons did the repair from the inside of the mouth. They cut back the tissue below the teeth and gums revealing the bone and the fracture. They spent a lot of time and energy getting the alignment just right before they placed the plate, with six 2mm wide and 15 mm long screws, to join the front of his mandible together.

This image from the internet gives a sense of what it looks like, but in the surgery I saw the fracture was midline and almost perfectly vertical with only 1 longer plate used.

This image from the internet gives a sense of what it looks like, but in the surgery I saw the fracture was midline and almost perfectly vertical with only 1 longer plate used.

They finished up at 2:40pm concluding the approximately 2-hour long surgery.

There was one more surgery on the board but after a long week of, finishing school, and graduation, I opted to go home at 3. Another varied and interesting day in the OR.

References:

- Madras J, Lapointe H (March 2008). “Keratocystic odontogenic tumour: reclassification of the odontogenic keratocyst from cyst to tumour”. J Can Dent Assoc. 74 (2): 165–165h. PMID 18353202.

- MacDonald-Jankowski, D S (2011). “Keratocystic odontogenic tumour: systematic review”. Dentomaxillofacial Radiology. 40 (1): 1–23. ISSN 0250-832X. doi:10.1259/dmfr/29949053.

May 22, 2017

Written by Jenny Luong (class of 2016-2017)

OREX always surprises me. It’s something new, something a little different each and every time.

Before the conference started, Dr. Harken was telling me about how many hospitals utilize Apache 2, a scale that estimates ICU mortality based on a number of laboratory values and patient signs, instead of the newer Apache 4 due to the cost. I believe he was going to talk about the test reliability and validity until residents started pouring in at 6:59 AM.

Dr. Harken began critiquing papers that studied the usage of pulmonary artery catheterization (PAC), which is the insertion of a catheter into a pulmonary artery. PAC allows the direct measurement of pressures in the right atrium, right ventricle, pulmonary artery, and the left atrium. While PAC is used to detect heart failure, the papers’ findings suggest that PAC is not very useful and has been linked to negative patient outcomes. I would have to read the papers to provide further detail, but Dr. Harken’s main message is to “question everything.” Just because a paper has over five thousand participants in it doesn’t mean that there isn’t selection bias or other such confounding factors.

I wandered into the OR alone and a little bit later than usual because there were some very lost looking families that needed to be taken to their appointments. I was awkwardly looking around and saw this blaring pink badge on someone’s chest that said, “MEDICAL STUDENT,” which meant, to me, they must be shadowing a surgeon = there is hope for me!

Matthew Crimp is currently doing his first surgical rotation at Highland, and introduced me to Dr. Berletti, who is simply amazing! In both surgeries I was to see today, she would be assisted by Dr. White. He was not as friendly, so I stayed out of his way. Dr. Reddy, the anesthesiologist is very kind and allowed me to stand near his area so I could watch.

The first operation was a bilateral ovarian cystectomy, as well as a diagnostic laparoscopy. The patient was an overweight 33 year old female. A small incision was made near the umbilicus (I think), and a tube was introduced. This tube was then connected to a machine that pumped oxygen into the abdomen, inflating it and allowing the doctors to see the insides clearly. Dr. Berletti and Dr. White used both palpation and scope to locate the ovaries and the cysts. It was strange seeing the needle for the local anesthetic on the other side of the abdominal wall. Several holes were made for moving the clamps and cutters around.

There were intestines and what looked like the top down view of a very small naked chicken (turned out to be the uterus…) and two hidden large white eggs. I have taken anatomy and I had no idea what I was looking at. I had THOUGHT that ovaries are smaller than that and were lumpy. Not round and egg-shaped. Until it hit me that this patient may probably need both taken out.

On the screen, I watched as Dr. Berletti lanced the left ovary and, I’m very proud of myself for this, did not wince as everyone else did when loads of yellow pus poured out into the internal cavity. Dr. White suctioned it up but had to rinse several times.

The right cyst was harder to get to. It was hard, slippery and swollen. After opening the ovary, Dr. Berletti was able to retrieve two pieces of the inside, asking the nurse to change this into a biopsy. The inside was crumbly and dark. The calcification was hard to get out, and so Dr. White suggested they leave it as it was attached to the peritoneal wall.

The clean-up of this involved some gel injected to help coagulate (?) the blood. After gauze and rinsing multiple times (also removal of hair), the main hole was stitched and the smaller ones were closed with adhesive glue.

The second operation was on 43 year old female, a laparoscopic bilateral tubal ligation. I had asked Dr. Berletti if I could follow her around for this. She left me in the prep room with Matthew and the patient. It was great talking to a patient who was so driven and optimistic. She wants to be a nurse and is now trying her best to finish prereqs.

This operation was finished very quickly. Because her ovaries are within normal limits, as are her tubes, the cauterization happened very quickly. Dr. Berletti even let me see the specimens after!

Today was a wonderful day. Doctors such as Dr. Berletti exude such competence and consideration that her patients feel at ease and her coworkers readily listen to her advice and input. I am always glad for OREX because I can be around people like her and have the opportunity to try to absorb some of their expertise.

April 6, 2017

Written by Courtney Pasco (class of 2016-2017)

When I got to the conference room this morning I was 90% sure they were not having rounds. No one had shown up when I got there at 7am and usually if I’m a minute late, I’m the last one there so I was a little thrown. Soon, though, I was joined by a couple of residents and a PA student named Libby. She and I got the chance to chat a bit about our backgrounds and I asked what made her choose PA school. She said that she was an EMT for a couple of years while she was decided what route she wanted to take, but ultimately that it was the flexibility of the PA profession that led her to her choice. She said that PAs don’t have to have a set specialty, they just get a job and get on-the-job experience which I totally didn’t know.

I saw three procedures today, all in OR 5, all performed primarily by resident Dr. Anne Hardy-Henry. The first procedure was a fistulotomy and when I introduced myself and said I was observing today she turned to me and said, ‘You chose a butt case?!’ The most striking thing about this case was how incredibly vulnerable the patient (a Latino male in his fifties) looked when he was in position. The surgeons and nurses positioned him and taped his legs before draping him so he was spread wide open with his legs in stirrups, under anesthesia, and undraped for about 15 minutes. The procedure itself only took 30 minutes. The basic premise is make an incision and access the fistula canal. Then insert a probe through the opening in the rectum and thread a rubber band through. Dr. Victorino was the attending and he explained to me this allows the fistula to drain and have a chance to heal, but that unfortunately it often doesn’t work.

The second surgery I saw was an inguinal hernia repair with mesh. I’ve noticed that I look forward to these abdominal cases, always forgetting that I’m never really able to see what’s happening. However, this case stood out for a different reason–the patient (also a Latino male in his fifties) proved very difficult to intubate. The first person to give it a try was an ER resident, John, doing his anesthesia rotation. After trying to fit the tube in for a minute, the nurse anesthetist practically shoved him out of the way, but she wasn’t able to intubate either. I was reminded of my last visit when Rebecca told me how intubation has gone south on her several times. In between tries they kept putting the mask back on him to keep his oxygen sats up. Finally, the anesthesiologist gave it a go and within 30 seconds, the man was finally intubated, though they remarked he would probably have a bad sore throat as a result of all of the attempts. The surgery got under way with Dr. Palmer attending this time, but I wasn’t really able to see much of anything. However, John came over and we got to chatting about our backgrounds and how he likes his career choices. He said that it’s been hard seeing his friends move into nice apartments, get married, have kids, etc. but now that he’s 30, a lot of them have also started to have ‘midlife crises,’ questioning whether they’ve made the right career choice and whether their work is fulfilling. “I’m never going to have that problem,” he said. He basically hit the nail on the head for what I’ve been worrying about with my career path–I want to do meaningful work, and while software engineering or web design will certainly be easier financially, emotionally, socially, romantically, etc. it may not be fulfilling. I don’t know if I can turn down something that actually helps people and that I am genuinely interested in and think I would be good at just because it would be easier if I did.

The last procedure I saw wasn’t technically surgical; the patient wasn’t on an OR bed or under general anesthesia. A morbidly obese woman came in on a BiPAP machine, in her ICU bed, and was put under conscious sedation for a leg debridement. I wasn’t expecting my Grey’s Anatomy experience from something that wasn’t even a surgery, but that was one of the more intense things I’ve ever seen. Her right inner thigh, lower leg, and top of the foot were all covered in yellow-gray tissue that needed to be removed. The surgeons didn’t want to keep her flesh exposed for too long so Dr. Hardy-Henry, Dr. Palmer, and Philip the med student all worked very quickly to remove it and they removed chunks of her flesh. It seemed like they were cutting away too much, but her leg was so large I think it wasn’t actually that deep. Up until this point I’ve been surprised at how bloodless the surgeries have really been. This, however, was like something out of a horror movie. Her skin was being cut and burned away, rivulets of blood were running down her leg and onto the bed, at one point there was literally a stream of blood like a small red fountain shooting out of her calf. It’s the most anxious I’ve felt since the first day in the OR, but I stuck it out and willed myself to get used to it. Once they finished debriding her leg, they needed to dress it. On her lower leg they did normal dressings, but on her thigh and foot they sewed in a special dressing made of pig tissue that the rep said could regrow skin even over bone and tendon. Each sheet of that dressing cost a couple grand. It was so impressive and expensive, Dr. Harken came in and got a picture with the dressing which definitely lightened the mood. I pushed myself out of my comfort zone with the leg debridement and realized I could still handle it, which is a huge relief.

April 1, 2017

Written by Cicily Cooper (class of 2016-2017)

I got to go to Grand Rounds which is my favorite. I’m so glad that I am free some Thursdays to get to experience it. I got to observe a debate about whether blood, specifically packed red blood cells can be used after 14 days with the same effectiveness as fresh blood. It was a very interesting and lively debate from two residents with entertaining and thought provoking introductions from Dr Harken. I left still being unsure whether blood after 14 days is just as good as fresh blood but I will agree pretty readily that it makes sense to use the oldest blood that is safe so that we do not throw precious blood away.

One of the doctors from the blood bank was there and she pretty heartily agreed that older blood is fine. It does seem like an arbitrary number in many ways though and she did agree that fresh blood is better. But, according to the clinical studies, it did not seem that blood older than 14 days had negative effects on outcomes. I bought it.

I got to the OR and some of the surgeries had already begun but I sneaked into a room that looked like it was just getting started. I got to see quite a few interesting surgeries. My first surgery of the day was an excision of a facial chin nevus (mole), done by Dr Allen who is a plastic surgeon. It was very interesting to watch this pretty small surgery and to watch Dr Allen talk through the nuances of repairing the area with such care so that scarring is minimal. I had not been to a surgery yet where plastics had been involved and it was interesting to see the extra care put into making sure that the person’s face was as unscarred as possible. I also got to meet Doug who is an FNP who works with Dr Allen. I was very excited to meet Doug because he went through the same program I am in a few years ago and told me a little bit about how he ended up in the OR. I was very excited to hear about his journey to becoming an RN first assist and then being the NP working with Dr Allen. I really appreciate getting opportunities to understand how people navigate to the places they end up within the world of Medicine. I love the idea of being an NP working in surgery so I was jazzed on this particular encounter. He also set me up with a stool and checked on me to be sure that I could see well and such. He did not directly participate in the operation though and so I would be curious to find out more what the NP’s role is in the OR. Hopefully I can ask him next time!

Next I walked into a laparoscopic bilateral salpingectomy, which I know has been described by other OREXers but is a removal of the fallopian tubes. I was enjoying watching it and then the nurse said “This is boring, go into room 4, there’s something really interesting happening there.”

I wanted to tell him that we’re not supposed to jump around the rooms, but he was insistent so I followed his advice.

He did not lead me astray. I stepped in and was a bit unsure what I was looking at but the surgical tech was quite chatty and told me that what I was looking at was a discectomy. I nodded even though I had no idea what that meant. Shortly the x-ray techs came in and then we all stepped out while they took a picture of the placement of Dr Patell’s tool. After they were done, the tech who I recognized from the ED asked me if I wanted to see. I said yes and he was able to explain to me that that x-ray was their third x-ray and that Dr Patell, a neurosurgeon, was trying to confirm placement between L5 and S1 to remove herniated disc. I was grateful for the learning moment and also for the warmth and helpfulness of all of the staff. The incision was quite small but they had a microscope and screen up so that the whole procedure was quite easy to see from my view point. Dr. Patell explained to me that it was usually much more straight forward than this because usually they are able to go straight in and this time they had to go in transverse to find the nerve to get it out of the way and then scrape out the disc. He seemed to be very quiet and focused but would occasionally explain something to me which only marginally helped me understand what I was seeing.

He eventually did locate the nerve and scooped it out of the way and then started scraping at the herniated disc to make space for the nerve. He eventually did and then stepped away as the resident closed the patient up with some help from the PA. Although it was certainly an interesting surgery, I found it quite challenging to understand what was going on and the whole neuro part of it pretty difficult to follow. I guess that is why neurosurgeons have to be in school so long (shout out to LUCY!!!).

I then had lunch and then came back to see one more surgery which was also by Dr Allen which was an excision of a right cheek mass. The operation was not dissimilar to the other removal but it was quite cool to watch the residents slowly cut around this mass and then the mass just kind of emerged from the person’s face. They also decided to do the person a favor and cut out another mole on the person’s face while they were at it (they were consented for it, and it was at the patient’s request). Again they carefully cut around and very carefully sewed it back, using extra care to suture in ways that would cause no additional scarring. It was pretty cool to watch both residents working on different parts of the face. I kept on wondering how they keep from poking themselves or each other with the sutures. I guess lots of practice.

Anyway, it was a great day!

Can’t wait until my next one!!

March 22, 2017

Written by Courtney Pasco (class of 2016-2017)

On my March OREX visit, I was able to see two laparoscopic surgeries before going home sick in the early afternoon (which I am just now getting over and why this write-up is so late—my apologies!!). The first was a laparoscopic salpingectomy of a Latina woman in her late forties. A salpingectomy is the medical term for removing Fallopian tubes. She mentioned she had already had kids and didn’t want any more. The nurse anesthetist on her case was Rebecca, who was wonderful to me. She was an ICU nurse for 12 years before she decided to make the jump to anesthesia and she hasn’t looked back since.

Rebecca told me to stand behind her during the intubation because she was doing it with the video monitor so she (and I!) could visualize her vocal cords. After the patient was intubated, Rebecca walked me through a lot of the medications she uses and the different things she monitors. She explained to me that they put the patient on 100% oxygen prior to intubation because if things go wrong, the patient’s lungs are saturated with oxygen and can feed off of that for a few minutes, buying the doctors some time. I asked her if things had ever gone south during one of her intubations. “Oh yeah. It happens all the time,” she said. I was taken aback. Granted I’ve only seen a few surgeries, but all of them had gone off without a hitch! This was no Grey’s Anatomy operating room. There are no monitors beeping wildly, no one has ever shouted “CLEAR,” and I’ve yet to be covered in blood. So to hear that complications aren’t as foreign as my experiences had led me to believe was a surprise. She explained to me that if the patient’s throat isn’t relaxed enough or they aren’t sedated enough, the airway will shut when she attempts to intubate and then even the oxygen mask won’t help to get them air. This intubation went smoothly, though, and once the patient was fully under, Rebecca switched her from a 100% oxygen to a 60% oxygen-nitrogen mix.

The surgeons then placed the patient in Trendelenburg and proceeded to drape her, keeping her pelvis exposed. They also placed a metal rod (for lack of a better description) in the patient’s vagina. I wasn’t totally clear on why, but I imagine it’s to angle/lift the reproductive organs for better exposure, like when a gynecologist palpates the ovaries with one hand in the vagina and one on the abdomen. The surgery was rather quick—exactly an hour from first incision to final closing. It would have been even shorter but the laparoscopic equivalent of the Bovie wasn’t actually functioning and they had to get a new one. The surgeons were able to sever the Fallopian tube at each end and then pull out the tissue (about 3 inches long) through the laparoscopic incisions.

The second surgery I saw was rather similar in some ways. Again it was a Latina woman in her late forties. Again it was a laparoscopic surgery on the reproductive organs. Again the patient was placed in Trendelenburg. However, this was to remove a mass on the patient’s ovary. The surgeons were discussing the possible outcomes they had talked about with the patient. They would try to cut away the mass and save the ovary, but they might have to remove the ovary and possibly parts of the Fallopian tube as well.

The surgery began simply enough; the surgeons recognized that they wouldn’t be able to save the ovary and so they severed it and then began the long process of attempting to pull it out through the patient’s belly button. For about twenty minutes, the surgeons cut, hacked, and snipped this mass. They were staring down at it in a bag through the patient’s belly button, but I couldn’t see a thing. They pulled out pieces of it and I thought to myself, “Okay so that must be like half of it, so now they’ll just pull out the bag.” It took them a little while longer, but when they finally pulled it out I was stunned. It was slightly smaller than my fist. They called pathology who came and took it away. I assumed pathology would get back to them in a few hours, maybe a day, but about twenty minutes later, as they were closing, he returned and told them it was extremely hard to cut because it was so calcified, but it seemed to be benign. He said he would freeze the sample and slice it and have a more definitive answer for them later, but that it was looking like good news.

Unfortunately, I cut my visit a little shorter than I had planned or wanted because I was feeling so crummy, but I was glad to have seen the cases I did and I left feeling amazed at how quick and non-invasive these laparoscopic surgeries were. The surgeons sutured the belly button incision, but for the others, they only had to use a glue! And while I am sure that the surgeons (who have front row seats) get to experience that awe of seeing inside of someone on every surgery, the view isMr not quite as impactful from a few feet back. However, for laparoscopic surgeries, I get to share in the awe and see exactly what the surgeons are seeing, following their discussions and decisions.

March 3, 2017

Written by Katie Darfler (class of 2016-2017)

During the morning discussion, Dr. Palmer talked us through two patients, one who passed away and one who survived. He started by suggesting that we be careful with labels and that if something feels off, we should investigate it thoroughly. About labels: be careful not to approach a patient with too specific of a label, because we may rule that a patient does not fit that label but then neglect to investigate other options. For example, approach a patient with abdominal pain rather than appendicitis because then the label will not rule out other possible etiologies.

The discussion seemed to center around how to approach patients and how to be effective in diagnosis. The first patient, who happened to pass away, experienced compartment syndrome which “occurs when excessive pressure builds up inside an enclosed muscle space in the body” (WebMD). Side note: compartment syndrome often occurs in the anterior compartment of the leg because the fascia is tough and, from what I remember, does not expand as well. Two common causes of compartment syndrome are: a crush injury and reperfusion (the action of restoring blood flow to an organ or tissue, typically after a heart attack or stroke). It turns out this patient had necrotizing fasciitis. Dr. Palmer showed us this patient’s CT scans to show us the compartment syndrome and then we discussed his numbers. We looked at his white count, his hemoglobin, his hematocrit, and his platelets as well as several other numbers including his lactate. I couldn’t jot them down quickly enough! Dr. Palmer encouraged us to start with a “wide differential” to consider all possibilities before ruling out other causes. The residents went through different options: cellulitis, etc. One interesting point was that no one number could function in isolation as a diagnosis, but that numbers in combination alerted the teams to areas of concern. We then discussed the second patient and had to move on to begin the surgery day.

Surgery #1: Vasectomy, Dr. Yamaguchi

The patient receiving the vasectomy had SVT (supraventricular tachycardia), so this normally outpatient procedure was done in the OR. I made sure not to miss the opportunity to observe the procedure. I noticed that the patient was visibly nervous about the procedure. As the team prepared the room, the CRNA calmed the patient down and provided him with systemic medication to prepare him for the vasectomy. Then, Yamaguchi injected local nerve block into the testicles and, after the surgery was fully prepared for, she began to feel around in the testicle for the vas deferens. She pulled it up to the surface under the skin and made a small incision. She then pulled the vas deferens out and snipped it. She then put the “bovie” in each end of the vas deferens and made some stitches before reinserting the snipped tubes back in the testicle. She stitched up the incisions and then put antibiotics on the outside of the testicles.

One of the OR techs was asking Dr. Yamaguchi if the procedure could be reversed and she indicated that it could be but is only effective 60% of the time. Additionally, having a vasectomy does not change sexual arousal. Dr. Yamaguchi also pointed out that a tubal ligation (female) is much more invasive, so a vasectomy is a logical choice for those who are ready to make that decision. (The more you know!)

Surgery #2: Left Knee Arthroplasty, Dr. Krosin

Wow. What a fascinating procedure! I had the opportunity to bump into Dr. Krosin in the hallway after the vasectomy, and I asked him where he was headed. After I indicated that I was interested in watching the knee replacement, he encouraged me to follow him. He then lead me into OR7 to observe a knee arthroplasty. By the time I arrived, the incision had already been made and the patella was pulled open to expose the ends of the femur and tibia. The cruciate ligaments had already been cut and the team was beginning to make measurements to decide how much of the femur and tibia needed to be sawed off in order to place the prosthetic knee. I was able to watch the team use drills and saws and mallets to shave down the bones and get them to their proper condition. Dr. Krosin explained to me that this part is extremely important as the prosthetic will need to move like a normal knee, so the bones not only need to be shaved but also need to be shaved at the right angle and right texture. At this point, one of the gentlemen working on her knee drilled down the center of the femur and a gush of blood shot up and out around the OR. I was splashed a little on my scrubs and the nurses were kind enough to help me clean up.

The men working on the patient’s knee kept checking alignment by bending her knee and moving it around after placing a temporary prosthetic for placement. They needed to saw off more bone, so they placed a device around the tibia with a slit along the side to insert the saw. Slices of bone came out. Throughout the procedure, there were so many tools and devices being used; it almost felt like a woodshop!

Once the doctors were content with the bone shavings, the width between the bones, and the proper prosthetic size, one of the residents began mixing cement. The cement was placed on the ends of the bones and the prosthetic caps were malleted into place on the bone. [Note: This procedure is not for the faint of heart, but I really enjoyed it!] Then, the doctors placed a plastic piece between the new end caps. It took a few tries to determine the proper plastic size piece, but they eventually found the one that worked best with knee movement. They hyperflexed the knee and wiggled it side to side discussing amongst themselves how the knee will loosen up over time and how to choose the proper size. They also put a plastic piece behind the kneecap to function as a type of tracker to keep the patella in line with the new knee.

Wow! Super cool procedure. Everyone was eager to teach and explain and answer my questions and I was so impressed with the collaborative nature of the OR. Very cool.